Multiple Sclerosis

Introduction

A study has shown that some of the disability associated with the early stages of multiple sclerosis could be reversed using stem cells. The treatment works by resetting patients’ immune systems using their own stem cells. While randomized clinical trials are still needed to confirm the findings, they offer new hope to people in the early stages of the disease who don’t respond to drug treatment.

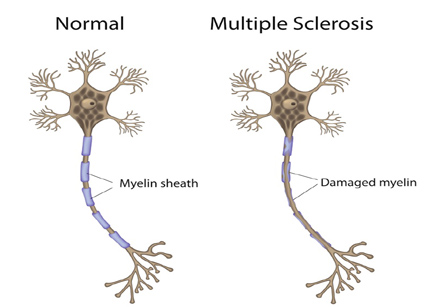

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease in which the fatty myelin sheath that wraps around nerve cells and speeds up their rate of transmission comes under attack from the body’s own defenses.

“These are very encouraging results, and it’s exciting to see that in this trial not only is progression of disability halted, but damage appears to be reversed,”

Iranian scientists have moved to the forefront in embryonic stem cell research, according to a recent joint study by Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Stem cells are primitive cells in the body that have the capacity to become any cell. Stem cells and bone marrow cells have been used since 1968 in patients with blood cancers like leukemia, aplastic anemia, lymphomas such as Hodgkin’s disease, multiple myeloma and even in ovarian and breast cancers.

Many of these stem cells can come from the cord blood or the blood in the umbilical cord that joins the baby to the mother in the womb. After birth the cord blood can be collected and processed to make stem cells into the desired cells. These cells can help in development of new blood vessels, increase the number of new cells.

Treatment

Richard Burt of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and his colleagues had previously tried using stem cells to reverse the process of MS in patients with advanced stages of the disease, with little success. “If you wait until there’s neuro-degeneration, you’re trying to close the barn door after the horse has already escaped,” says Burt. What you really want to do is stop the autoimmune attack before it causes nerve-cell damage, he adds.

In the latest trial, his team recruited 12 women and 11 men in the early relapsing-remitting stage of MS, who had not responded to treatment with the drug, interferon beta, after six months. They removed stem cells from the patients’ bone marrow, and then used chemicals to destroy all existing immune cells in the body, before re-injecting the stem cells. These then developed into naïve immune cells that do not see myelin as alien, and hence do not attack it.

Three years later, 17 of the patients had improved by at least one point on a standard disability scale, while none of the patients had deteriorated.

Burt cautions that more trials are needed to confirm the findings – and these are now underway – but eventually, stem cell transplantation could provide an alternative to drugs in patients who don’t respond to them. Transplantation also has the benefit of being a one-off treatment.

“These are very encouraging results, and it’s exciting to see that in this trial not only is progression of disability halted, but damage appears to be reversed,” says Doug Brown at the UK’s MS Society.